Overview: Our financial and monetary institutions systemically deepen economic inequality

What if you were told that we are approaching another global financial crisis that will be worse and more prolonged than the global financial crisis of 2008? Would you want to know more? What if you were told that for a number of decades now, our financial and monetary institutions have been some of the greatest contributors to income inequality all over the globe? Would you be interested in understanding why?

What if you were told that for decades now, many regulations that are intended to strengthen our financial systems, or interest rate decisions that are intended to stimulate the economy also had a silent but harmful impact on your future wealth? And that in the process it effectively enforces the reduction of government debt by silently eroding the wealth of everyday savers? What if you were told that over time, your retirement savings hold even less real value than what your financial advisor may realise? Would you believe that all this stems from the monetary policies that are influenced and implemented by senior political and central banking leaders, whom we trust for the sound functioning of our economies?

The inconvenient truth

The unfortunate truth is that the above statements can be factually substantiated. It is not only the more commonly-experienced irritations such as bank fees, remittance fees or investment fees that affect our pockets. In the background, there is a silent and subtle redistribution of wealth away from everyday savers like you and I, towards profligate governments and financial institutions. This redistribution of wealth becomes more pronounced with higher rates of inflation. And inflation need not be high (relative to historical rates). It is not only the highly publicized hyperinflation scenarios of Venezuela or Zimbabwe that demonstrate how wasteful government expenditure and unsound monetary decisions can destroy peoples’ lives.

Even in well-developed economies such as the US, characterised by moderate economic growth, low interest rates and seemingly harmless low inflation rates, the wealth and savings of people are being systemically eroded. In most countries, people entrust their money, savings and economic well-being to large financial institutions and central bankers. People have faith that a strong regulatory environment in their country will support their endeavours to survive (or even thrive) financially. Yet these very regulations and decision-makers in whom we trust create the very money supply, inflation and interest rates conditions that stealthily move wealth from private sector savers to public sector debtors. So the next time you think that topics of inflation and government debt/wastage are boring and shouldn’t concern you, think again.

How deep does the rabbit hole go?

Instinctively, many of us are aware that something is wrong with the status quo. We feel the discomfort and inequity when we experience:

- Exorbitant remittance fees for sending money to our home country,

- High interest rates on our personal or business loans,

- Exorbitant payment fees, whether it is accepting a card payment or making a cross-border corporate payment,

- Limitations on how much money we can invest offshore, and

- When we experience reductions in the value of our portfolios while asset managers, brokers or exchanges continue to thrive, to name a few.

However, the rabbit hole goes way beyond this. Our financial systems and regulatory frameworks have been architected in such a way that money and the wealth generated from it, insidiously moves through the banking system, away from savers towards financial institutions and governments. More importantly, the scale at which this takes place is mind-blowing. This article will provide an objective, fact-based overview of how all of this takes place. Hopefully, it will ‘open your eyes’ to these realities and push you to think of better alternatives to what has always been considered as normal.

…we are approaching another global financial crisis…

all this stems from the monetary policies implemented by senior political and central banking leaders who we trust for the sound functioning of our economies…

It is not only … hyperinflation scenarios of Venezuela or Zimbabwe that demonstrate … unsound monetary decisions can destroy peoples’ lives.

Even in well-developed economies … regulations and decision-makers in whom we trust create … inflation and interest rate conditions that move wealth from private savers to public debtors.

The following major themes will be explored:

- Consumers bear the brunt of the heavy cost structures of today’s financial systems.

- Financial institutions benefit more from their clients’ money than what clients do.

- Even in well-functioning, developed economies, wealth is redistributed from the poor to the rich.

The article will start with the more commonly-experienced financial services ‘irritations’ that we have become so accustomed and desensitized to. Thereafter we’ll venture into how the monetary institutions and systems that we trust every day facilitates the insidious and hidden transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich. All of these issues and challenges will then provide the basis for why we need a better system of money.

In general, many of us are unaware of the extent of the difficulties and challenges that companies offering some kind of financial service have to deal with. Everywhere across the globe, the actual financial markets, technology platforms and systems within those markets are fragmented and disconnected to varying degrees, even in developed economies. As a result, the many different service providers often come together and collaborate in order to provide us with a particular service.

For example, in order for you to make a simple card payment at your favourite store, there are companies that provide the point-of-sale devices to accept your card payment, the bank with which your store has a bank account – called the acquiring bank – a card network such as Visa, Mastercard or Amex, to transmit your payment authorisation request to your issuing bank, your own bank – called the issuing bank – who eventually will transfer funds from your account, and a central bank that will ensure that acquiring and issuing banks’ payment obligations are cleared and settled. This is not an exhaustive list, but it becomes easy to how all of these parties and their own costs will contribute to the overall cost of just processing a simple payment.

Many costly service providers are required to facilitate payments…

…all of these parties and their own costs will contribute to the overall cost of just processing a simple payment.

Inevitably though, we feel the effects of those challenges in our everyday lives in the form of exorbitant banking fees, insurance premiums and reduced savings or investment returns. However, besides having multiple players, each adding their costs/fees for their portion of the service offering, many other factors add to the cost burdens that inevitably is borne by the consumer. Let’s examine a few:

Financial institutions have to maintain costly infrastructure

Large banks, insurance companies and other financial institutions usually carry massive costs for things like:

- The regional network of branches, with each branch incurring the costs of its staff, the premises, management of cash, and so forth;

- The regional network of ATMs, which incur the costs of maintenance, cash replenishment, cash transport and security to name a few;

- The majority of banks have ageing legacy IT systems with many IT professionals, dedicated to its maintenance and ongoing enhancements;

- Tens or even hundreds of thousands of well-paid employees;

- Financial Services executive salaries are typically very high;

- Etc.

In short, traditional financial institutions are extremely costly to run, and these costs need to be recovered through fees, premiums, interest and so forth.

Massive head office and branch costs, ageing and costly IT infrastructures, and high executive salaries all add up, and are passed on to the consumer.

Disconnected infrastructure adds to the costs of servicing customers

In addition to financial institutions being costly to run, the fact that their systems are not well integrated adds to their costs. This lack of standardised and integrated systems is the reason why for example:

- It can take a few days for a payment to your recipient to reflect in their bank account;

- You are not able to get one view of all of your investments and insurance policies held by different institutions, without an intermediary or broker that manually needs to collate this for you. And of course, this intermediary will require a fee for the service.

Global payment systems are as fragmented as domestic ones

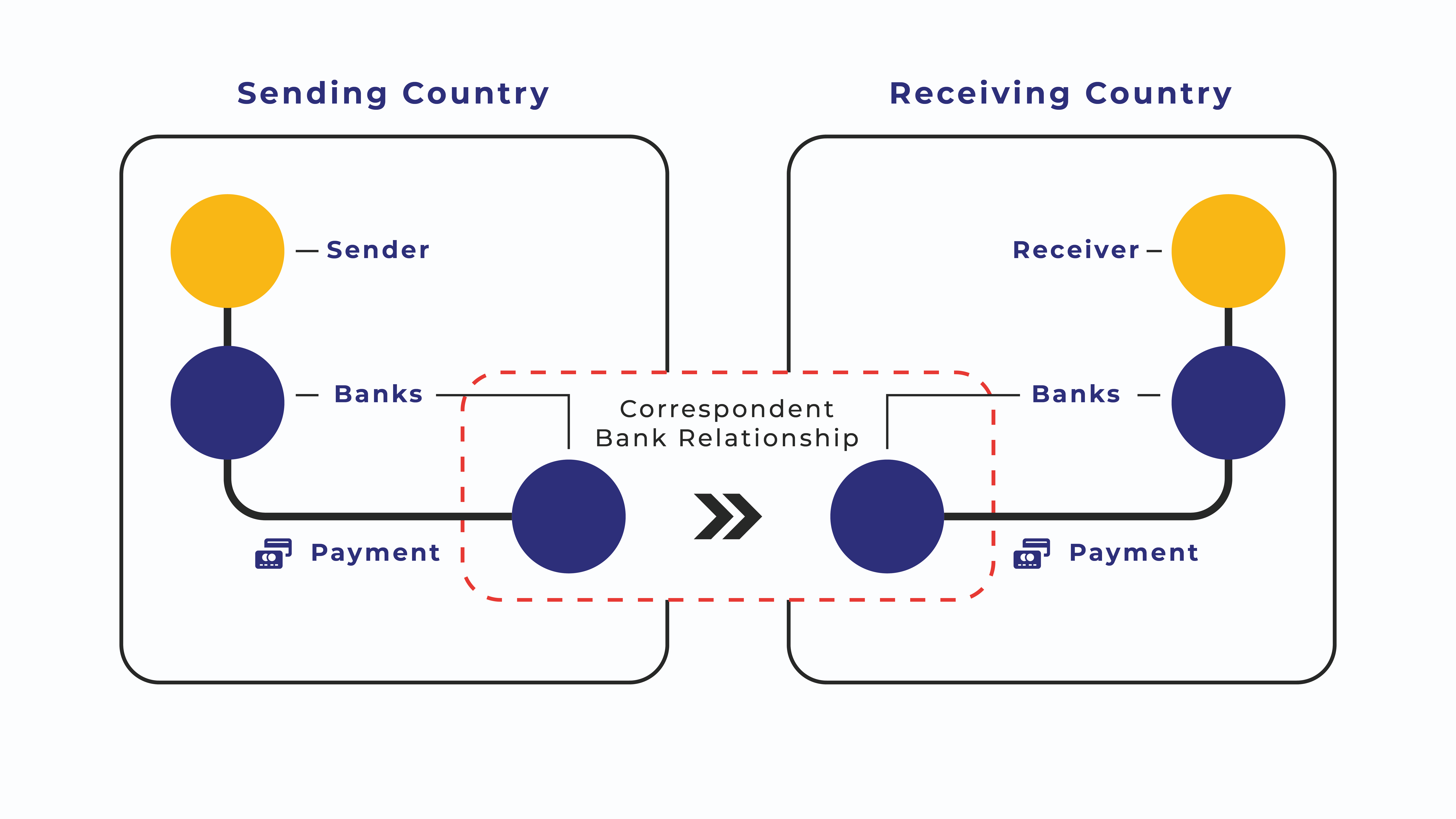

The lack of integration becomes more pronounced when you take a global perspective. Individual countries’ domestic payment system are not integrated and geared to handle streamlined cross-border payments. As a result, additional intermediaries such as the SWIFT network and correspondent banks, each charging a fee, are required to facilitate cross-border payments.

In addition to financial institutions being costly to run, the fact that their systems are not well integrated adds to their costs. This lack of standardised and integrated systems is the reason why for example:

- It can take a few days for a payment to your recipient to reflect in their bank account;

- You are not able to get one view of all of your investments and insurance policies held by different institutions, without an intermediary or broker that manually needs to collate this for you. And of course, this intermediary will require a fee for the service.

Additional intermediaries such as the SWIFT network and correspondent banks add to high costs of cross-border corporate payments.

The global average cost for remitting $200 remains high at about 7%, with the banks on average being the most expensive at 11%

Global payment systems are as fragmented as domestic ones

The lack of integration becomes more pronounced when you take a global perspective. Individual countries’ domestic payment system are not integrated and geared to handle streamlined cross-border payments. As a result, additional intermediaries such as the SWIFT network and correspondent banks, each charging a fee, are required to facilitate cross-border payments.

Cross-border payments are just some of the use-cases where Bitcoin technology comes into its own. Global remittance payments reached $689 billion in 2018. The global average cost for remitting $200 remains high at about 7%, with the banks on average being the most expensive at 11%. More detail about remittance costs can be found here.

Cross-border corporate payments are significantly higher in value. In 2018, cross-border corporate payments exceeded $21 trillion. Fees that average between $30 – $40 per payment, along with an average currency spread of 2% make cross-border corporate/B2B payments very lucrative for financial institutions. In cases where corporate treasurers rely on the receiving bank to handle currency conversions, visibility into exchange rates and conversion fees can be limited for both the sender and receiver of a B2B transaction. Cross-border payments do not settle real-time – settlement times of up to 5 days is not uncommon. However, the inability for both the sender and receiver to effectively track the progress of funds as it moves through the correspondent banking system is generally a bigger concern for corporate treasurers.

Fragmented systems in the investment industry

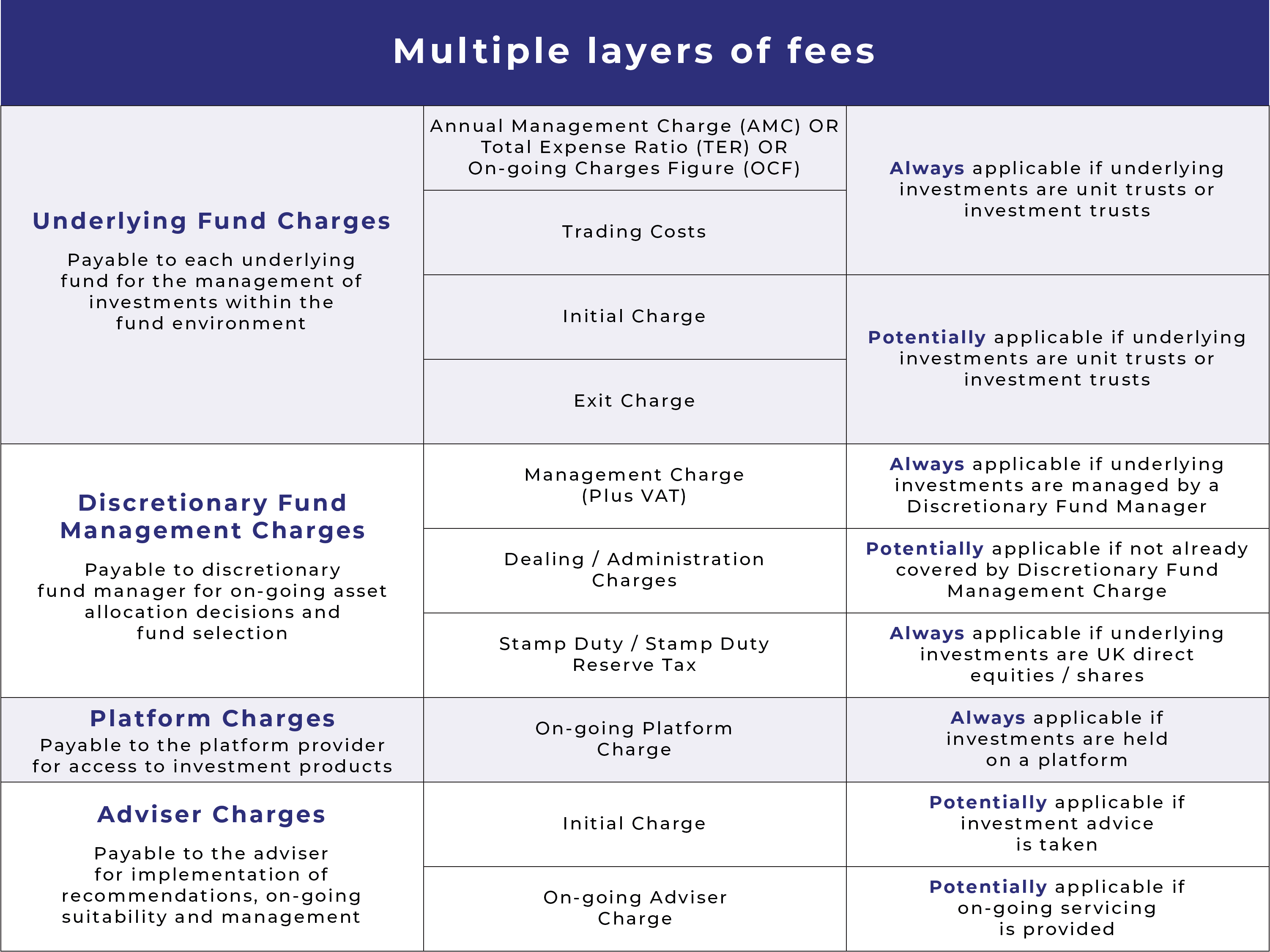

Other ways in which fragmented systems impact consumers can be seen in the investment space. Multiple parties collaborate in the management of your investments, all of whom charge fees that ultimately reduces your investment returns.

Consider the investment returns you expect from your retirement funds. Behind the scenes there are quite a few participants involved in the process of managing your retirement funds, each of them charging fees for their services:

- A retirement fund administrator – the administrator assists with:

- Channelling portions of your monthly salary deductions to the different asset managers that will manage (and hopefully grow) your funds,

- Channelling portions of your money to an insurer for your group insurance benefits,

- manage claim payouts, transferring your funds to other retirement vehicles, and so forth;

- Asset managers – they will invest your monthly contributions into specific shares and other instruments, usually based on some form of life-stage investment strategy:

- In addition to their normal asset management fee, they may charge a performance fee if the portfolio performance exceeds some benchmark (which investors rarely understand).

- Separate (and usually higher) fees are charged for the portion of your investments that are invested offshore.

- Multi-managers – multi-managers may sometimes be involved in the management of your investments by managing the underlying investment managers who each manage certain portions of your investments. An additional multi-manager is then levied for this service.

- Platform providers – these providers have the systems and operations to give more savvy retirement fund members more choice in terms of where to invest their contributions. Platform fees are levied for this as well.

- Employee benefits brokers – their responsibility is to help your employer with the structuring of your retirement benefits, be the interface with the administrator, assist with educating you (the employee) about how to better grow your retirement savings, and so forth.

- Asset consultants – these consultants typically advise stand-alone retirement funds with regard to investment strategies and levy a fee for this advisory service.

And of course, there are other entities such as the exchanges where the actual buying and selling of securities take place. These exchange and trading-related costs are all passed on to the investor as well. Today still, in the 21st century, the issue of opaque and exorbitant investment fees is still one of tremendous frustration.

Adherence to regulations increase the cost burden

Financial institutions are generally tightly regulated to ensure that customers are adequately protected. The result is that banks, insurance companies etc. need to staff highly-paid legal and regulatory experts to ensure that all internal business activities always comply with regulatory requirements. Other, highly-paid professionals such as actuaries and chartered accountants are also employed to ensure that the institution manages this regulatory-enforced capital.

Unintended consequences of these high-cost structures

Unequal access to banking services

One of the unintended consequences of the above costs is that it is not feasible for everyone to be banked. Banks need to maintain profitability, and low-cost accounts for low-income earners are almost always unprofitable for them. It is estimated that roughly 2 billion people across the globe are unbanked.

Low-cost bank accounts for low-income earners are unprofitable for banks. This is one reason why roughly 2 billion people around the world are unbanked.

Unequal access to investment opportunities

Another unintended consequence is that not everyone can afford the same investment opportunities. For example, in order to access investment opportunities abroad through your local broker, there are usually minimum investment amounts that less affluent people are not able to afford. Or even more simply, some people are not able to access the services of certain money managers unless they have some minimum amount of money available to invest. Less affluent people, therefore, have limited investment choices that do not offer the same advantages that are afforded to wealthier individuals. They typically would only have access to simple products such as:

- Investing in a collective investment scheme – Despite the fact that funds are pooled, the various fee items still greatly impact on investment returns.

- Investing in a notice account at a bank – Unfortunately, these accounts offer interest that barely (if at all) keeps up with inflation.

Institutions benefit more from clients’ money than clients themselves

Banks benefit more from their customers’ money than what customers do

Investment-related institutions earn revenue regardless of market movements

The average investor that invests in a unit trust or buys listed shares via a broker will bear the risk of market/price movements. The broker and the exchange involved in the investment process will gain volume-based transaction fees even when markets plunge.

Customers pay bank fees for a bank account and do not earn interest on their bank account balances. But banks use customers’ money to issue loans from which they earn interest revenue.

Investor wealth is reduced in declining markets. But brokers, investment managers and exchanges earn fees even when markets plunge.

Asset managers who manage investment portfolios for individuals or even retirement funds will earn a fee of say 1% of the assets they manage, regardless of whether their customers’ portfolios reduce in value. This is another example of how the average investor’s benefit is tied to market movements, but the asset manager’s income is not (at least not in the short-term, because continuous under-performance will result in the asset manager losing business).

Insurances houses gain more than consumers

Beyond the well-publicized economic crises

Now let’s turn our attention to more boring and abstract topics such as government debt and inflation. Some of us may watch the news relating to central banks’ decisions about interest rates because these decisions directly affect our everyday debt repayment obligations. But very few of us would watch news relating to government debt or inflation. These matters are just too far removed from our daily lives, and so far beyond our spheres of influence that we could not be bothered with it. However, the impact of government debt and inflation on us is so profound or even life-changing that it is surprising that this does not receive more media attention.

Those of us who are privileged enough not to have suffered from it, often think of the highly publicized economic crises such as the financial crisis of 2008 and the hyperinflation in countries like Zimbabwe and Venezuela as once-off or infrequent events. Anomalies. And as a result, those of us with thriving careers in ‘well-functioning economies’ do not appreciate the significance of the flaws in our monetary systems and how government debt, interest rates and inflation-targeting is managed. Every day, an economic phenomenon known as Financial Repression plays out in even well-developed economies.

Financial Repression represents the worst form of financial oppression because it redistributes wealth from the poor to the wealthy and wasteful governments in the most unnoticeable of ways. It makes use of regulatory and economic policies that take the guise of prudential regulation rather than the politically-incorrect label of financial repression.

Financial Repression

Financial Repression is a term that describes the regulatory measures that result in the subtle channelling of funds from the savings of citizens to governments in order to to reduce their debt burdens. Financial Repression has been extensively studied and documented but has fallen into obscurity since the end of the “financial repression era” in the 1980s. It has been widely ‘forgotten’ that the widespread system of financial repression that prevailed for several decades (1945-1980s) played an instrumental role in reducing the massive amount of national debt that many advanced countries accumulated during World War II. Government debt was reduced by subtly moving wealth from citizens and savers towards the repayment of government debt, without the political consequences that would have ensued if for example austerity measures were adopted.

Financial Repression was effected through a number of regulatory tools that governments have (and still do) employed to pay off their debt by using private-sector savings, such as those of retirement/pension funds and other individual savings.

How it works

Financial repression takes place by instituting banking and regulatory mechanisms that result in the money owned by citizens finding its way through the banking system to alleviate government debt burdens. Furthermore, policy and regulatory tools ensure that the bulk of these savings are directed towards the funding of government debt, as opposed to being directed to other avenues such as precious metals or offshore investments.

Very simplistically, governments will borrow money from central banks to finance their operations (military, healthcare, education, etc.), at relatively low interest rates. Central banks, in turn, will provide these loans by borrowing from banks at similarly low interest rates. And banks, in turn, will minimize the impact of the low-interest income they receive from central banks, by paying even less or no interest to bank account holders. The net effect is that the central bank and its member-banks escape and pass on the cost of these government loans to bank customers.

Furthermore, regulatory tools will ensure that the bulk of the private sector savings continue to be directed towards government debt rather than other more profitable investment avenues. For example, many pension funds are by law limited to how much money can be invested offshore. Pension fund regulations will generally have limitations for how much can be invested in particular asset classes, but generally have no limit for how much can be invested in government bonds. A global survey of the regulation of pension funds conducted in 2017 can be found here.

The use of private savings to pay off government debt is enabled using the following tools:

Policy and regulatory tools that enable financial repression

- Explicit or indirect caps or ceilings on interest rates, particularly those on government debts. These interest rate ceilings could be effected in various ways including:

- Explicit government regulation – Regulation Q in the United States prohibited banks from paying interest on demand deposits and capped interest rates on saving deposits).

- Central bank interest rate targets (often at the directive of the Treasury or Ministry of Finance when central bank independence was limited or nonexistent).

- Creation or maintenance of a captive domestic market for government debt, achieved by requiring banks to hold government debt via capital requirements, or by prohibiting or disincentivising alternatives. These include:

- “Prudential” regulatory measures requiring that institutions (almost exclusively domestic ones) hold government debts in their portfolios (pension funds have historically been a primary target).

- Transaction taxes on equities also acted to direct investors toward government debt instruments.

- Prohibitions on gold transactions.

- Government restrictions on the transfer of assets abroad through the imposition of capital controls.

Along with a steady dose of inflation, the above tools facilitates the transfer of well from savers to reduce governments’ debt burdens.

Adding inflation to the mix

When the interest repayment on the government loan is lower than the inflation rate, the negative real (inflation-adjusted) interest repayment results in the erosion or liquidation of the real value of government debt. This document, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, describes this economic phenomenon and its sweeping impacts on society in detail.

Negative real interest rates strongly reduce government debt burdens because:

- The interest repayments on government loans are very low compared to other rates in the market. But in addition,

- Inflation results in increased tax revenue for governments through capital gains tax as well as VAT and income tax which increase commensurately with salary increases.

Over time, the size of debt repayments vs. tax income reduces substantially. Negative real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates erode the real value of government debt, but also results in the destruction of the real value of individuals’ savings. The policy tools above force savers to participate in this economic environment, by minimising their abilities to invest in other, inflation-beating avenues such as commodity or offshore investments.

Financial repression is sometimes referred to as a stealth tax. The above policy tools creates a mandatory, regulation-driven ‘captive market’ where a combination of innocuously low interest rates and somewhat higher rates of inflation directs private savings towards the reduction of public debts in a manner that is complex and opaque enough that the average voter never understands how it works, or is even aware it is happening. During the financial repression era, vast sums of wealth were redistributed away from savers with virtually no political consequences.

Financial repression still persists today

The mechanics of repression are still at play today, but not as overtly and to the extent that it was during the financial repression era. For example, Regulation Q has been abolished and restriction on the purchases of precious metals have mostly disappeared. However, restrictions on offshore investments still exist in many countries today.

Financial institutions such as insurance companies and banks are incentivised, or even compelled to hold a certain amount of low-yield government debt. On numerous occasions, banks are subsidizing the liquidation of government debt by being forced to hold government bonds with interest repayments that are less than the rate of inflation. Banks, however, are able to escape the negative impact on their income statements by:

- Using their customers’ deposits in bank/cheque accounts to issue loans to the public at rates much higher than that of a government bond;

- Paying little or no interest to its cheque account customers.

Banks are able to generate interest from loans (using their customers’ money) or invest in high-return assets (using their customers’ money) to not only liquidate government debt, but also to earn profits despite this.

Impact on society

The extent of the impact of financial repression tools on individual savings depends on where the money is invested or held. Money being held in a bank account where no interest is earned simply loses its value through inflation. Money being held in a risk-free notice account will enjoy moderate interest rates. But if the real rates are negative, the value of this money is also eroded by the power of inflation.

Investors continually strive for inflation-beating returns by investing in equities for example. But even after you have been able to earn inflation-beating returns, your returns may be subject to capital gains tax, which immediately destroys your net returns to some extent.

To give you a sense of how sweeping the results of financial repression are on a nation, let’s consider the United States and the UK. During the financial repression era, both of these economies were on average able to liquidate government debt by around 3-4% of GDP. In 1980, the US GDP was about $2,86 trillion. 4% of this roughly $114 billion.

When it comes to stimulating the economy by maintaining a healthy rate of inflation, say 2%, by reducing interest rates, central banks set in motion exactly what is needed to liquidate government debt. Specifically, low interest rates combined a moderate rate of inflation. 2% may seem harmless, but its impact compounds over time. For example, a $1000 investment earning say 5% return over a 20-year period will be worth about $2650 at the end of the 20 years. However, an inflation rate of 2% will, in fact, reduce the real value of that investment by 32%, to around $1800.

The next financial crisis

The decade that preceded the outbreak of the subprime crisis in the summer of 2007 produced a record surge in private debt in many advanced economies, including the United States. Now, post this crisis, government debt is becoming alarmingly large. According to the International Monetary Fund, the global debt to GDP level is 250% – around 30 percentage points higher than it was on the eve of the 2008 financial crisis. The size of the risky US leveraged loan market has doubled to more than $1.2tn from around $600bn on the eve of the 2008 recession.

Why Bitcoin?

We have become accustomed and desensitized to inequity introduced by our financial systems that we have forgotten that there may be better alternatives. These deficiencies have become ‘normal’ for us. This is why we just carry on with life as normal, and have come to accept these things as necessary evils that are part of life. We can no longer conceive of alternatives to the wasteful bureaucracy of governments.

This is where Bitcoin (and not any of the other cryptocurrencies) comes into its own. Bitcoin is a new form of money, with a limited supply that cannot be tampered with. The limited supply of bitcoins (21 million) makes it unsusceptible to inflationary pressure. The Bitcoin network is completely censorship-resistant, and cannot be influenced by any powerful government or corporation. It is a form of money that is global, transnational and not under the jurisdiction of any country. And it is a form of money that can be transmitted without intermediaries. The transmission of bitcoin transactions cannot even be stopped if the entire Internet was shut down. It is a remarkable technology that represents the most significant advances in Computer Science since the advent of the Internet.

Why Bitcoin?

Why not Ripple? Why not central bank cryptocurrencies? These will be the topics of future blogs.